Table of Contents

Back in the ‘70s, USDA Secretary Earl Butz urged farmers to plant commodity crops "fence row to fence row" and told us "[a]dapt or die." It was bad enough when USDA Secretary Ezra Taft Benson told farmers (in the ‘50's) to "get big or get out," but “adapt or die”?

No matter: US farmers were listening to these two guys - because getting big and planting fence row to fence row became gospel. Farms, almost all of them, have become very specialized. Most function as part of the animal production chain, either housing and feeding cattle, pigs, and poultry, many of them under contractual agreements with corporate processors, or growing the grain commodities (corn and soy) for all those animals to eat.

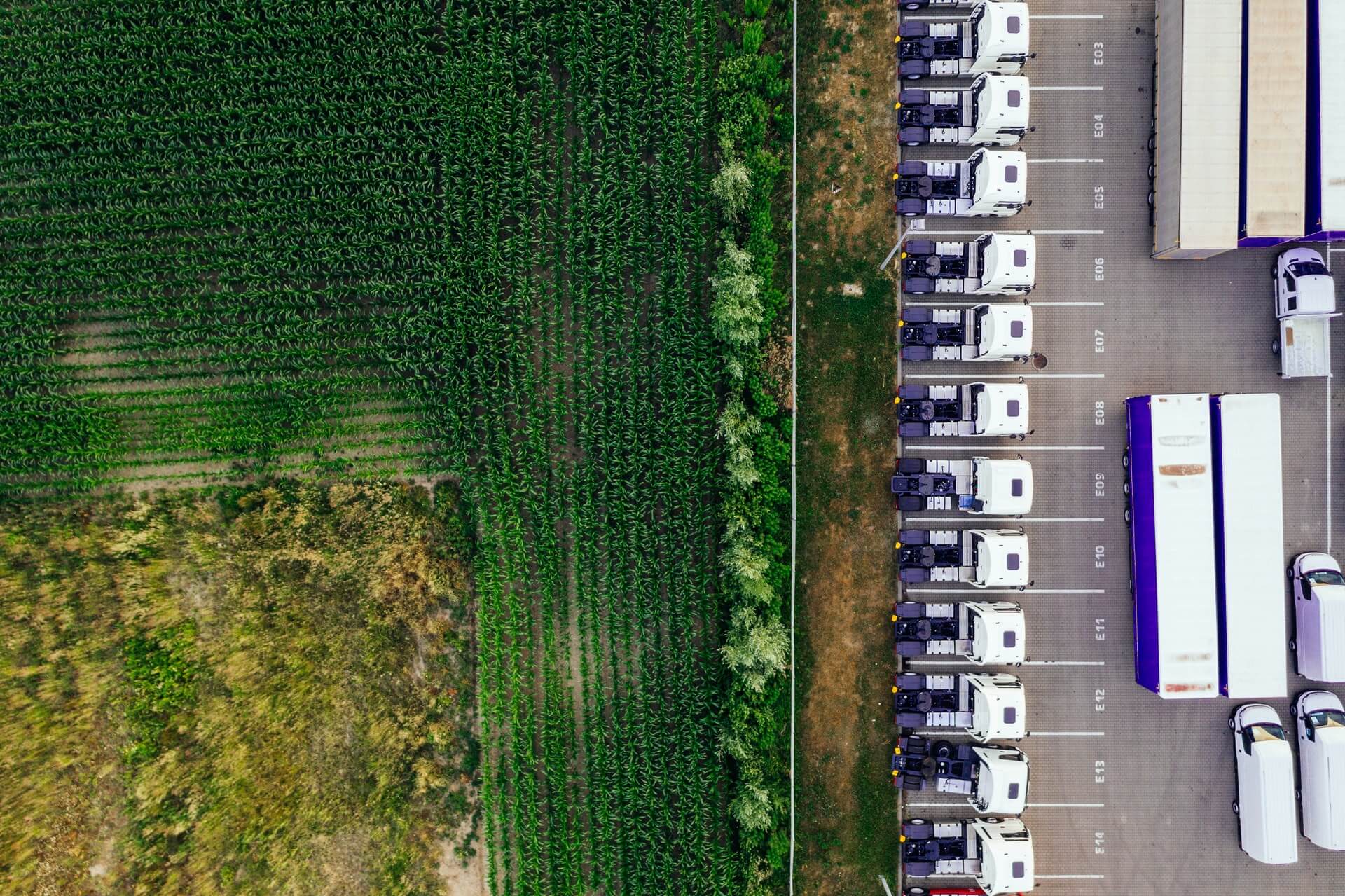

Commodity crop farms have gotten large – thousands of acres, corn one year and soy the next, in an endless rotation. Animals are often raised in Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs), which confine thousands of animals, either in specialized buildings or outdoor feedlots, such that animals seldom have access to pasture, outdoors, fresh air, or natural light.

Feed may be grown miles or states away from the CAFO, making the system very fossil fuel intensive. Since manure is mostly water, hauling it long distances is not cost effective, so CAFO operators may find it impossible to apply the manure according to safe environmental limits, making excessive application their cost-effective option. In lieu of manure being available locally, grain farmers buy commercial fertilizer, which is petroleum-based and again, fossil fuel intensive. Hardly a sustainable system when compared to integrated small farms growing their own crops and recycling their manure as fertilizer on their own fields.

Specialized manure-holding facilities are required, but due to the large volumes produced, heavy rain, snow, storage leaks, or improper handling, CAFOs create a very real potential for big manure spills. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) notes that living or working near a CAFO can be potentially hazardous to your health. Manure can contain antibiotics, pathogens, nitrates, pesticides, hormones, trace elements, and heavy metals, all potentially dangerous, especially if they enter drinking water.

Smaller, More Diverse Farms Are the Answer

Contrary to what the “get big or get out” crowd would have us believe, CAFOs and industrial agriculture are not necessary to properly nourish humanity. Small farms are typically more efficient food producers, especially in developing countries. These non-U.S. small operations farm their land more intensively and rely on a mix of grain, vegetable, and fruit crops, in addition to keeping livestock on pasture, which thereby can achieve 50 to 300% greater output per acre, while still farming in a sustainable manner.

Those who farm in the US distance themselves from the term “peasant,” thinking it connotes a tenant, sharecropper, small farmer, or mere farm worker. I was a small farmer; a peasant and proud of it. Remember, roughly half of the world's population are farmers who work the land and tend livestock. As a small farmer, I was a minority in the US, but worldwide, I was part of the majority.

The vast majority of the world's small farmers and farm workers struggle against the power of trans-national agribusiness corporations (TNCs) that control the vast corn/soy monocultures and the CAFOs, and thereby control the world's food supply. Peasant farmers struggle against oppressive government policies that, by design, convert local farming and food economies to industrialized agriculture, with much of the production intended for export markets.

Peasant farmers struggle for the right to grow what they wish, for access to water, land and credit, and for the rights of women farmers who still feed most of the world. They struggle for protection from subsidized foreign imports and to protect their crops from contamination by Genetically Engineered (GE) seed. They struggle to eliminate food from international trade agreements, because food is different - food is a human right, not a commodity.

US farmers are ambivalent to this struggle, but are we really so distant from it? Do we really control our own destiny? An Iowa farmer notes that in his state farmers own about 20 percent of the land they farm, while 80 percent is rented. They are tenants.

We Are Controlled by the Middleman

We have no control over our market prices or our input costs, but the TNCs do. Young and beginning farmers are generally priced out of land purchasing, and government subsidy programs dictate what crops we will grow. Without a subsidy check, there is no reason to grow commodity crops domestically because they are cheaper on the world market. Farmers do what they have to do to survive. We compete with farmers worldwide to see who can work the cheapest while the global market crushes local food production.

There is no shame in being a peasant, a farmer, in struggling to control your destiny; manual labor and working the land are not demeaning. Feeding your family, your community and resisting the globalization of food are the struggles all farmers – all people – must share, whether they grow millet and rice in India, herd cattle in Africa, grow tomatoes in a Brooklyn window box, or fish the North Sea.

Yet, with food having been debased to the status of an international commodity, it is viewed in strict economic terms, both by the shopper looking for bargains at the supermarket and by the stock traders who deal in pork bellies, unit trains of corn, and cargo ships full of GE soy.

Commodities are fine in the financial world, but they have no place in our bellies. Wall Street couldn't care less how many varieties of corn are cultivated in Mexico or Guatemala or for how many thousands of years they provided both physical and spiritual sustenance.

The fact that we place little value on our food, or that it no longer gives us the sense of home and community that it once did, goes to the heart of the problem. We have lost control of our food system, as consumers and as farmers. Apathy about our food, where it was grown, who grew it, what's been added to it, is an open invitation for corporate interests to take control. We handed them the keys to the pantry and told them, in effect, to make their profits however they wished – just keep the shelves full.

Since we have seldom seen empty store shelves and as most of us in the Global North can afford to buy whatever we wish, we generally accept the bounty of the industrial food system. Further, many are prone to enthusiastically support that system when we accept the myth that the system is really essential in order to “feed the world.”

Food Is Way More Than a Commodity

And there’s the rub: feeding the world was never the intention. In the 1970s, well-meaning researchers and eager graduate students, myself included, were convinced we could eliminate hunger in our lifetime. Yet the big picture was always about corporate profit, and people with good intentions who genuinely wanted to end hunger generally didn’t think much about that. All those hungry masses were seldom given the chance to feed themselves. In reality, there was never a shortage of food in the world as a whole: there were areas of food shortage, just as there were areas of obesity and food waste. Most areas that lacked food also lacked real Democracy and certainly, as we see today, there was a constantly growing income gap.

While we became spectacularly good at growing commodities to feed the livestock for our meat-heavy diets, fuel our cars, and create processed food, we were not producing enough real food for people. For that we depend on underpaid immigrant labor to produce our fruits and vegetables, as well as imports from the very parts of the world where food access is a problem.

Ethically, we cannot continue to source our food from the rest of the world because those farmers have no option but to work for poverty wages to supply the global market, nor can we continue to allow land-grabs to push small farmers off their land. At the price of the environment, we cannot continue to encourage and subsidize industrial agriculture and continue to feed grass-eating animals a diet of grain.

Solutions Can Benefit Farmers and Consumers

To really address the ongoing failures of the food system – failures highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic – and to position ourselves to adequately face the next crisis, we must reform our food system, ensure fair farm prices and empower peasant farmers and agricultural workers while we invest in rural infrastructure.

All farmers need fair markets and fair prices. The government must, as it has in the past, establish reserves for grains, as well as other products. Non-recourse government loans – a part of previous Farm Bills – would allow farmers to sell their produce either on the market or into the reserves, with their decision based on a floor price that, under a fair pricing system, farmers, processors, and retailers could all live with. Reserves would improve prices for farmers, prevent food shortages and stabilize consumer prices.

Supply management is an essential part of a fair pricing system, either as a quota to cap production at a certain level or actually taking a certain number of acres out of production. The idea that we can no longer expect other countries to absorb our excess production which undercuts their farmers, should go hand-in-hand with restricting imports that could undercut prices and the well-being of US farmers.

By investing in smaller, local processing facilities – for beef, dairy, as well as for fruits and vegetables – we could strengthen markets and make the supply chain more flexible. This investment should include more brick-and-mortar facilities, as well as mobile facilities that can travel from farm to farm, giving farmers multiple options for sales and consumers more options as to how they buy.

Photo by Megan Markham on Unsplash

Photo by Megan Markham on Unsplash

In sum, we need to reclaim our food system from the speculators, the corporations, and the international financial institutions that pressure farmers to grow commodities instead of food. It’s time we started producing more food locally again and let the rest of the world do likewise. Time we found the nearest farmers’ market, supported urban agriculture, and planted those window-boxes in Brooklyn and everywhere else. Time to eat like our health really depends on it, because it does. Time we started thinking about food in the big picture rather than whatever happens to be on our plate at the moment, not knowing the story of that food, or worse, not caring.