Table of Contents

In April 2017, we got a startling wake-up call. A large butter processor, Grassland Dairy Products Inc., based in Greenwood, Wisconsin, sent form letters to 58 dairy farmers, abruptly stating that they would no longer be picking up the milk from their farms effective in 30 days. Over the next year, other farmers in Wisconsin and other states received similar letters from their processors.

My husband and I dairy farm with his family in Columbia County, Wisconsin. We milk 400 cows on the farm that has been in his family for over 100 years. Fortunately, we did not receive one of these letters. However, this was a startling new reality for us. Wisconsin farmers have benefitted over the recent decades from a relatively robust and distributed network of cooperatively owned and private processing infrastructure. In the past, farmers had choices of where to send their milk and often had processors coming to them, wooing them to switch, to get more milk on their truck routes to fill butter churns and cheese vats.

Dairy Farmers Are in Crisis

After the notification from Grassland Dairy Products Inc, farmers, milk haulers, processors, advocates and state government officials came together and were able to find new homes for the displaced milk from the Grassland farmers. The immediate crisis for those individual farms was perhaps averted, but the larger, structural issue was still looming: Farmers were producing more milk than the processors and marketers could move. This was a main cause of the low prices paid to farmers, plaguing the industry and accelerating dairy farmers exiting the business, or worse yet, declaring bankruptcy. The vicious cycle of too much milk, leading to low prices, where only bigger and bigger farms can survive, which then leads to more milk produced, continues to speed up. It is important to note, that this trend towards fewer but larger farms, also has ecological implications. Concentrating more and more animals in fewer places also concentrates the ecological risk. The manure management and nutrient loading, when not properly managed poses increased risks to water quality, both groundwater and surface water.

The 2017 shock came two years into a five-year price trough for farmers. Dairy farmers, and most US commodity farmers, for that matter, are used to low price periods, but at least in dairy the price cycles normally were limited to one or two years of low prices, followed by a corresponding up-cycle of higher prices. Using loans and savings, farmers could usually weather the low-price “storms.” But this time, there has been no upswing. Other than some one- or two-month blips of higher prices along the way, dairy farmers have been burdened with prices well below their cost of production. It is no surprise then that Wisconsin has seen a record loss of dairy farms.

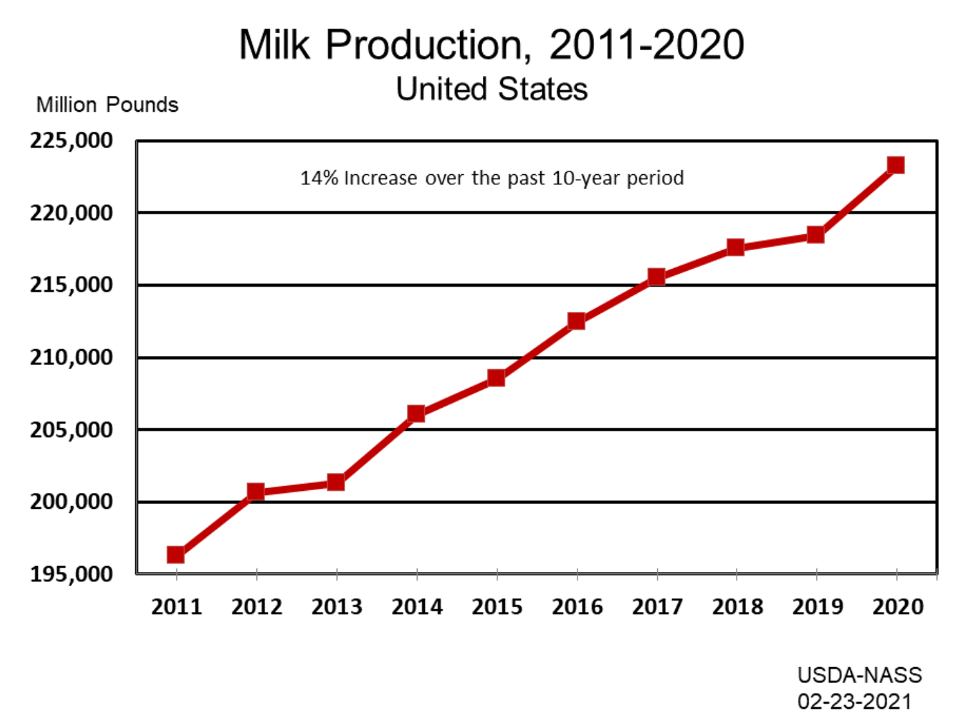

What is perhaps a surprise to the casual observer is that through this time of record low prices and farm loss, overall dairy production has in fact continued to rise [figure on production increase from NASS].

I took Economics 101 in college and was taught that if “the market” was sending farmers a consistent low-price signal, that should cause a supply reaction to back off of production to create some scarcity that would lift the price back up to some supposed equilibrium. Clearly that textbook equilibrium was not functioning on the ground. It looks nice in your economics textbook, but in reality, the signals are not working that way and farmers are going broke.

Dairy Together and the Farmer-Led Movement

While most of the farmers jolted by the Grassland letter found a short-term solution and were picked up by other processors, the underlying issue of continued overproduction has not been addressed. Farmers are chronically operating in a surplus market. A coordinated supply response is needed. Instead of looking on the demand side, through checkoff efforts promoting consumer consumption and expanding exports, farmers are coming together to organize on the supply side, focusing on the need to manage supply to balance with actual demand. This is not a new concept even in contemporary times. For example, cranberry growers and potato growers have used it over the years in the United States. And we see a variety of systems in other countries to provide supply side solutions.

Towards this end, in 2017 the Wisconsin Farmers Union began a concerted effort to build a farmer-led movement to call for important reforms to address the underlying issue of oversupply with the clear goal of supporting family farms with a fair price for their milk. This work is being done under the banner of Dairy Together.

Towards this end, in 2017 the Wisconsin Farmers Union began a concerted effort to build a farmer-led movement to call for important reforms to address the underlying issue of oversupply with the clear goal of supporting family farms with a fair price for their milk. This work is being done under the banner of Dairy Together.

Dairy Together is focused on building power in the policy and market arenas by building a durable coalition of farmers, farm organizations, allied consumer and environmental organizations, and supply chain partners to:

- Engage dairy farmers in discussions and peer-to-peer information sharing about dairy policy and strategies to address financial stress and policy options

- Establish a farmer network to support shared communications and messaging about the emerging economic situation and potential strategies for short and longer-term action

- Provide opportunities for farmers to build consensus and raise the visibility of their concerns within their dairy co-ops and various public forums

- Identify and contract for research opportunities that support policy and organizing

Growing Our Coalition

This work was officially kickstarted in March 2018 with a set of meetings around Wisconsin, bringing farmers together to hear from their Canadian dairy farmer peers about the way the Canadian coordinated system works by matching supply with demand. The plan is not to replicate the Canadian system, but to learn lessons from our neighbors to the north. The meetings then expanded out to other states, including Minnesota, Michigan, Vermont, New York, California, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and beyond. Farmers and advocates from Wisconsin and Michigan also took an August 2018 bus trip out to Albany, New York to meet up with other farmers and advocates to talk dairy price policy reform, convened by the Agri-Mark Dairy Cooperative. The gathering drew over 400 people and a number of different possible policy mechanisms were discussed.

The Dairy Together organizing efforts have brought together state Farmers Union chapters from around the country, as well as the National Farmers Organization, which was a co-partner on the “Dairy Together Road Show,” the California Dairy Coalition, and Farm Aid, which sponsored the bus trip and also featured the issue at the 2019 Farm Aid Concert at Alpine Valley in Wisconsin. In addition, the Northeast Organic Farming Association, some state and local chapters of the Farm Bureau, and National Family Farm Coalition and some of its member organizations have been actively involved in the conversations.

Considering a ‘Market Access Fee’

Part of this effort included commissioning dairy economists Mark Stephenson from UW-Madison and Chuck Nicholson, then at Cornell University, to reexamine a model created during the 2012 Farm Bill discussions as part of efforts spearheaded by the Holstein Association, which included a “Market Access Fee” as a main policy driver. The policy format is not a Canadian quota system; however, it does establish a base level of production per farm. Farmers wishing to expand beyond that base pay a fee for additional production units; a federal administration would be charged with pooling the fees and distribute them back to the farmers that did not expand beyond their base. The idea is that the fee would be a disincentive to increased production and would provide a higher price for those not expanding and adding to surplus production.

The Market Access Fee mechanism is by no means the only policy that would achieve the goals of farmer-led efforts to establish fair prices for farmers and balance supply with demand. It has been the one that has been most examined in this process and it is a policy that was included in past Farm Bill deliberations, receiving bipartisan support, although not achieving passage into law and regulation.

Dairy Together’s Policy Goals

Dairy Together, with facilitation by Wisconsin Farmers Union staff, convenes regular national calls of farmers and coalition partners to discuss the policy mechanisms and the strategy to push decision makers in the industry and the government to adopt a supply management system. Coalition members have also traveled to Washington, DC to talk to lawmakers about the need for supply management to protect family farms. The coalition has not yet presented a final detailed policy proposal, instead continuing to bring additional partners to the table and knowing that any federal law or regulation will need to go through the official policy making process.

The bulleted list below outlines the key aspects of each policy that has been agreed upon by the farmers and organizations that have come together through the Dairy Together movement:

- Provide a fair price

- Reduce price volatility

- Address overproduction

- Have provisions to discourage consolidation

- Allow for new farmers to enter without a huge financial hurdle

- If using a base level of production – that it is designed to discourage the base from acquiring value

- Be mandatory – no opt-out clauses

- Be national

- Be coupled with short-term action to sustain farmers until longer-term structural change can be enacted

- Address import and export issues and lead to smart trade policy

- Have meaningful farmer input in development, implementation and governance

More Farms, Not Bigger Farms

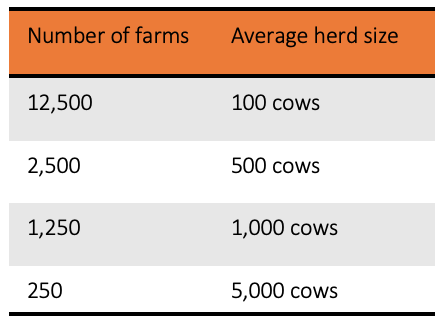

The goal of the Dairy Together efforts are to support family farms with a viable and fair price, so that farmers can stay in business and be active members of their communities in a distributed and diverse structure of production. In 2019, Wisconsin dairy farms produced over 30.6 billion pounds of milk. The average Wisconsin cow produced over 24,152 pounds of milk a year in 2019. To maintain 30.6 billion pounds of annual production, we need approximately 1,267,000 cows. Using round numbers, here is an example of the different sizes of farms that can produce 30 billion pounds of milk in Wisconsin:

Wisconsin, and the rest of the United States, can choose between two means of production: one in which many, small and mid-scale farms can exist independently, or the other in which very few farms can exist with large herds. Considering the and outcomes of very large farms, the Dairy Together effort opts for the variant that includes more farms, not bigger farms.

Dairy Together: Building a Farmer-Led Movement for Supply Management by Sarah Lloyd is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0