Share this Post

Table of Contents

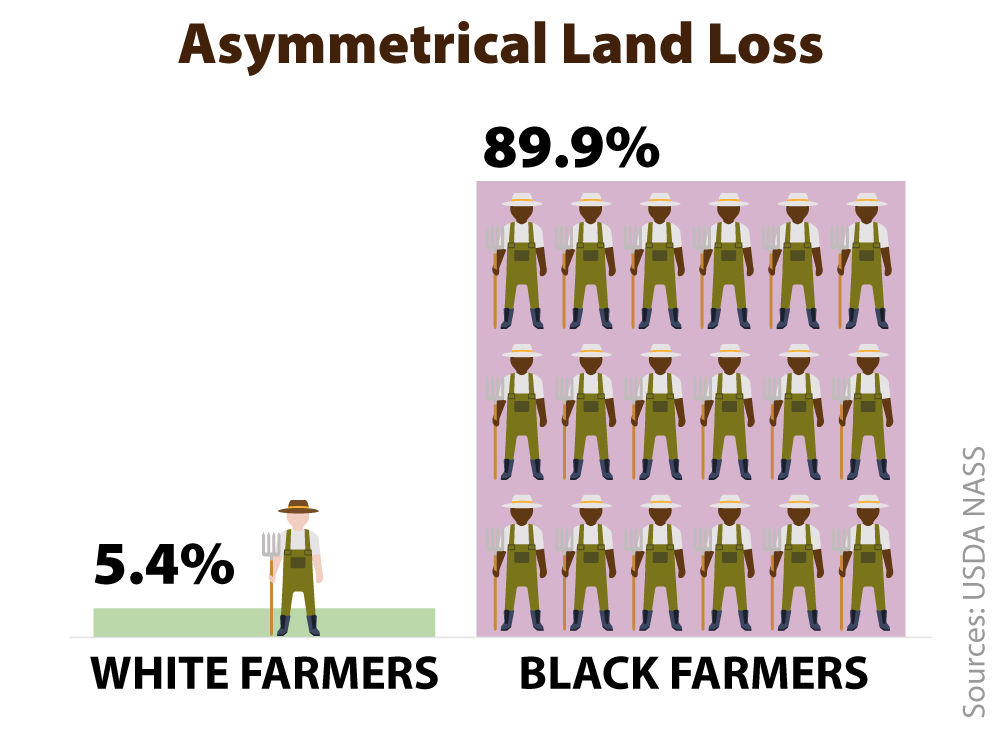

My perspective on this is not that of someone from a farm. I came from a family that lost land, and that is one of the reasons that I am not from a farm like many of the Black folks that I work with. So, I talk about this from the standpoint of land loss in the Black community. I grew up in an all-Black community, where we didn't own the infrastructure. We rented the housing. We didn't own the businesses. Historically, the only thing that was owned—in most of our communities; especially the community I come from—was the church.

I am from two different sides of this conversation. On my mother’s side, the family owned land in Lowndes County, Alabama. That land was passed down to my grandfather, my mother’s father. He passed it down to his children, my mother being one of seven children. So it was Heirs Property (link to glossary). But as my mother grew up, they ended up losing the land before I even learned about it. Like most folks, you have this land that has been passed down from generations. And then the disconnect happens because of the tenure of land being so insecure. So, we lost that land. I started understanding it once I became part of the Federation of Southern Cooperatives. And all the conversations I heard from my grandmother on my mother’s side were about working the fields of some of the plantations. At that time, there were a lot of cotton plantations around Montgomery and a lot of industry. My grandmother would talk about work in the fields. The conversations I had with her weren’t on the farmers’ side, and it was such a disconnect when you resorted to just working somebody else’s land. So, those conversations were never around ‘parity.’ They were about mistreatment on the farm, how little they got paid being labor on various farms and in that system.

On my father’s side, the family came from a place called Hatchechubbee and has been fortunate enough to keep the land in the family. We have family reunions on my father’s side every year, so we grew up understanding that there was land. There weren’t many conversations related to it in reference to farming it. The elders dealt with the work on it. We have business meetings at the family reunion each year, but mostly about how to keep the land in the family, not about farming it. So much has happened over the years - the farming side disappeared. I’ll explain why.

Coalition Building with the Federation of Southern Cooperatives

That brings me to my journey to the Federation. Once I spent time with farmers, and co-workers, that is when I started understanding the issues—the why. I came to this organization with a lot of questions more than anything, and wondering what had happened to our land, and the land of Black farmers, people and communities. I started connecting the dots. I then started hearing about these issues of parity and price support floors. I come to this work from that disconnect from the land—from not knowing why we lost it.

Once I got to the Federation, I started hearing and having conversations with some of our board members. One of the board members was a farmer from Kentucky. At that time, tobacco was king. And we were always hearing that losing their quotas and losing the price support was the downfall of their farm, and Black farmers eventually losing land and losing farms. I heard the conversations with peanut growers in Georgia, talking about how they relied on price support and quotas around peanuts and issues from other farmers in Mississippi having a whole different conversation around farming fresh fruits and vegetables and not having any kind of support around those crops.

Across the board, however, there was a perception that Black farmers were getting less from their quotas—they did have quotas—but they were receiving less from their quotas than their white counterparts. So they always felt there was some discrimination even within the quota system. There were many meetings at the Federation, especially during the annual meeting, with the USDA. A lot of the Federation meetings would be coordinated to have USDA there or we arranged for the farmers to testify before Congress. We would bring busloads of farmers—Black farmers—from Kentucky, Georgia, Tennessee to voice their concerns about low prices and unfair treatment to the USDA. I particularly remember when Ms. Mattie Mack, from Kentucky, testified about how the tobacco quota system was supposed to raise prices, but the big tobacco buyers would force small farmers, and especially Black farmers, out of business. There were constant conversations about this in the 1990s and 2000s.

In a 1996 interview, long-time FSC/LAF (Federation of Southern Cooperatives/Land Assistance Fund) president Ralph Paige decried the ‘Freedom to Farm’ (alternatively: ‘Freedom to Fail’) Farm Bill as “devastating.” Turning the racist mid-90s discourse on its head, Paige lambasted it as “nothing more than a welfare program that would pay large corporate farmers to grow fence-row to fence-row.” Paige astutely predicted its dangerous impacts: “It does not have a safety-net in this bill that would protect family farmers for the long-run. It has decreasing payments that will fade out in seven years. The small farmers who have small acreage and small allotments will be the ones who are hurt most because their payments will be very small and would fade out quickly. For instance, the Peanut Program should not be tampered with because it does keep farmers on the land and many poor people in rural communities especially in Georgia, Alabama, and South Carolina derive a living from the Peanut Program. Either they are working in plants or they are farm laborers, or they grow peanuts.”

I came on to the Federation in 1997, and these conversations were very powerful. We are just now archiving this advocacy, in our Amistad archives, digitizing these testimonies. The Federation certainly participated in the farm justice movements, and the whole creation of FarmAid, with Carolyn Mugar and others. The Federation was instrumental in founding FarmAid, working to center Black farmer struggles in the farm justice movement.

For half a century, the Federation’s advocacy attests to the urgency of fair prices for Black farmers. Yet, we do not use the term “parity”—why? The word does not speak to the needs and lived experiences of our members. For a select, elder few who recall the cotton, peanut, or tobacco quota programs from a generation or two ago, like Mr. Ben Burkett, the concept of price-floors and supply management make sense. But for middle-age or younger farmers, the concept is historic and improbable. Moreover, for those struggling to hold on to land, or who have suffered the trauma of racist dispossession, ‘parity’ seems too abstract and removed from the urgency at hand. They are ready, however, to resume prior activism around fair prices—alongside the struggle against broader racisms in agriculture and land policies.

Why and how did the issue of prices become peripheral to Federation advocacy? I think people were worn down. There have been a multitude of issues, a lot of focus and resources diverted to the farm crisis in general and the plight of Black farmers, because of the urgency of the situation. Facing rampant discrimination and lack of access to credit, our minds were pulled off the parity issue. Lawsuits, different fights, all required so many resources. Even more than the Federation had at that time. There is a lack of common knowledge, and major disconnects in these movements. We understand things differently; we talk about things differently. Also, many in the Black farming community don’t speak of it in terms of parity, but rather as a fair price. Someone like Ben who sits on the board of the National Family Farm Coalition and hears the term and uses it, but for others, if you talk about parity, you’ve lost people. It is considered a dirty word by some; a word with too much baggage. But fair prices resonate, very much. Equity resonates even more. There has to be equity in policing, education, but also in the food system.

There has to be equity in policing, education, but also in the food system.

The Discrimination Black Farmers in America Experience

Having a conversation about fair prices can happen once we get to the level playing field, to the base line. Only then can we talk about prices and fair prices.

Having a conversation about fair prices can happen once we get to the level playing field, to the base line. Only then can we talk about prices and fair prices. That’s a much-needed conversation, but we have to start by maintaining the land base first, and then credit and debt. Until then, and unfortunately, talking about fair prices is almost like a luxury.

And that is the shame in all of this. This gets in the way of even how we collaborate. It’s like you bring in a football team together, and you want to talk about what plays we have, but some of the players don’t even have the proper gear to be out there—they don’t even have a helmet on. They are worried about how to play the game safely, before they worry about the right way of running a play. And that prevents you from operating as a team because you have so many players out there at different levels. Until you get all the players on the team at the same level, it is hard for them to operate effectively as a team. All of that is to say we can’t show up in coalitions the way we need to at times because we are dealing with some things that are so fundamental that they get taken for granted.

It has to be put in the same context of what is happening today, right now with all this unrest and these protests in our country. At the heart of it is police brutality. It’s been about discrimination. At the center of it all, it has been about unfair treatment,

inequities, inequalities, about how the police treat Black people specifically and people of color in general. We watched a Black man die on television, on social media, at the hands of someone who was supposed to serve and protect.

Now, I say all of this because some of our friends—and I underscore the word friends because that’s exactly how they behave and how they have shown themselves to be said, ‘I didn’t realize this [racist police brutality] was still going on today. I thought this was something we got through in the 60s and 70s. And my response is, Black people have been living this every day since then, just in different ways.

One of the things, on a personal level, I also had to come to grips with is that my son, who is 27 years old and graduated from college a few years

ago is in that high risk group and extremely vulnerable to these issues of brutality and unfair treatment of people of color. His college project was a video on this exact same thing. You would think he did it today—as a response to what is going on now. It was an awakening moment for me because I had to realize that, wow, my son was away in college, in a place where I thought he was sheltered; and he was dealing with the same reality that every kid on the street, every Black kid, deals with every day, that we all deal with, without shelter—even in protected environments. And this is not always seen or understood, even by our friends. And that’s why this moment is so important because people are beginning to see this for what it is and see things they may have missed over the years. And we’re starting to have real conversations.

When friends come together, it is extremely important for friends to understand where each stands at that moment, and what each is dealing with. They need to understand the players on the team who are not ready to talk about the plays because they are still trying to get the proper equipment to go out there and play the game.

Messaging Parity in a Language People Can Relate To: Equity

This is all to say that parity is sometimes not understood and not the language used by all. Equality, equity, and fair prices may be better words. Even when it is understood, it is a luxury. I don’t say this to minimize it, because it is extremely important. We just have to understand that in order to get to this important part of it, some other players on the team, some other members of the coalition have other urgent issues that they see as something they have to get past before they can even get to this.

We have to focus on all of these issues. How do we wrap this up into the context of what is going on right now? We have to treat everybody, every farmer, fairly, within the contexts of policing, healthcare, education, etc. But even when it gets down to pricing & land access; we must wrap these issues up in the blanket of racial equity at large—and deal with them that way. People should understand that first you have to secure land, for Black farmers, Black landowners—this is key. Even when that land tenure is secured, they have to maintain it. And the only way to maintain it is with fair prices, which are extremely important. Because if you get to the point, to have land and good tenure of it, you still have to make it productive. And there’s no way to make it productive unless you are getting a fair price—unless you are getting a floor at the very start. This is extremely important, but we have to make sure we are framing it the right way and that we are paying attention to all the needs of everybody, so that everybody around the table is equipped to fight for this issue.

Cooperatives are extremely important to this issue of parity, when you are looking at the cost of production as the basis. At the end of the day we are talking about how do we make sure somebody gets a fair price. And in order for the price to be fair, it has to first take into consideration the cost of production, and then from there, it adds on to some reasonable profit in order to make a living. So, getting at that cost of production is important because when you start talking about a small farmer—well, most farmers, especially Black farmers—they're buying in a retail market but selling in a wholesale market. When it should be just the opposite. Usually, large farmers, corporations and others, they buy wholesale and they sell retail. But small farms are in an inverse situation, buying inputs at a retail store, and then selling product at low wholesale prices. They're already behind the eight ball.

What the cooperatives allow small farms to do--especially Black farmers and those with limited resources--is to aggregate things. To aggregate and share the tools & equipment that they have. But more importantly, aggregate production. They can buy collectively and gain economies of scale, then lower the costs of production. And the more you can lower the cost of production, the easier it becomes to get to that fair price. It then allows them to start buying in a wholesale market and hopefully, sell in the retail market.

Farming as a Civil Service

Parity programs and quotas are worth revisiting. But until we start looking at farming as a civil service, we will always be chasing our tails. If we as a country, as a collective body of people start understanding farming and agriculture as a civil service, we will understand the need for the government to be engaged.

What makes us unique as a country is that we operate under the common good. And the challenge is finding out what are the themes that we all have in common and food is surely one of them. If we are operating from the standpoint of the common good of food, and supporting those who are growing food, then it becomes obvious that there has to be a quota. So the question of quotas and what it takes to provide a fair price floor has to begin with the recognition of farming as a civil service to this country.

The history and layers of this struggle for equity—from land to credit to fair prices for Black farmers—needs to be gathered and archived. We are working with the Amistad Archive at Tulane University to collect and archive our materials. More needs to be written down and recorded. One thing my grandmother used to always say was that you either spend time writing about it or doing it, and sometimes you can’t do both. That is why I truly value the researchers, the writers, because without those folks, this work doesn’t go anywhere and it is just our internal operation, and nobody knows about what we are doing. We haven’t had the resources to employ someone who can be sitting around writing about the work. So we depend upon these relationships.

My perspective on these issues is truly guided by this organization, and by the things that I’ve learned from various mentors throughout this organization, including Ralph Paige, John Zippert, Ben Burkett and others. And also by the voice of our membership, because I'm constantly meeting with our board who comes directly out of the membership. And because our director

of communication is constantly speaking with the membership and trying to survey them and learn from them. So, my words are reflective of that. But all of this is not usually written down.

And I’m not an anomaly here. Ralph Paige, Charles Prejean and all of the leaders whose words and work need to be chronicled and recalled. There are things that have been written about the

Federation’s work, and its work on fair prices for Black farmers, but it is usually others who’ve had the opportunity to talk with people and write it down. Our

challenge is also archiving that.