Authors: Jacqueline Krikorian (American University School of International Service practicum grad student), Gerardo Bueso (American University School of International Service practicum grad student), Maria Moreira (World Farmers, Rural Coalition), and Jessy Gill (World Farmers)

Table of Contents

Introduction

In order to achieve, or even dream, of updating parity through national policy, we must look towards the leadership of community-based agrarian justice groups that are implementing parity principles on a micro-scale. World Farmers, an esteemed leader within the Rural Coalition, stands as a grassroots, community-based immigrant and refugee farmer support organization. Though they do not use the term parity explicitly, they are providing a model for how to shift from disparity to parity with their innovative, resourceful, and generative ethics of cooperative marketing, supply coordination, and collective bargaining of price floors. Updating parity policies and programs for intersectional justice and agroecological production will require learning from such organizations and their needs, constraints, and articulations of collaborative agrarian viability.

Although the 1996 Farm Bill ended price floors for farmers, a variety of supply management techniques, including grain reserves, non-recourse loans, set-asides, price bands or targets comparable to a commodity support level, and cooperative organization had long worked to derail cyclical overproduction. From a consumer perspective, central media has described farm ‘subsidies’ as the token policy of agrarian support, but in reality these interventions are the antithesis of true parity, supporting agribusinesses far more than small and mid-scale farms. Government subsidy payments made to farmers acted, and continue to serve, as dollar-bill sized bandages on the oozing wounds of supply mismanagement. Though left with the least power, those trying to make a living from farming are the ones who bear most of the burden for the failings, high prices, and inaccessibility of our current food system. As with any enterprise in a free market economy, this blame is falsely attributed. The principal "choice" a farmer has is to increase scale and mechanization in an attempt to meet the low farmgate price, or go out of business.

Current Models of Cooperatives, Coalitions, and Grassroots Parity Organizing

To counter this grinding, downward pressure on prices and increasing stress on farmers, farmworkers, and farmland, growers have sought collaborative solutions and developed a range of agricultural cooperatives. In general, cooperatives emerge to offset the failings of unfettered capitalist markets as well as the failings of government to right these market wrongs. Working with a social ethic as well, they expand the focus from solely policy incentives to a broader paradigmatic shift, organizing agrarian communities against the impossible situations they have been presented with.

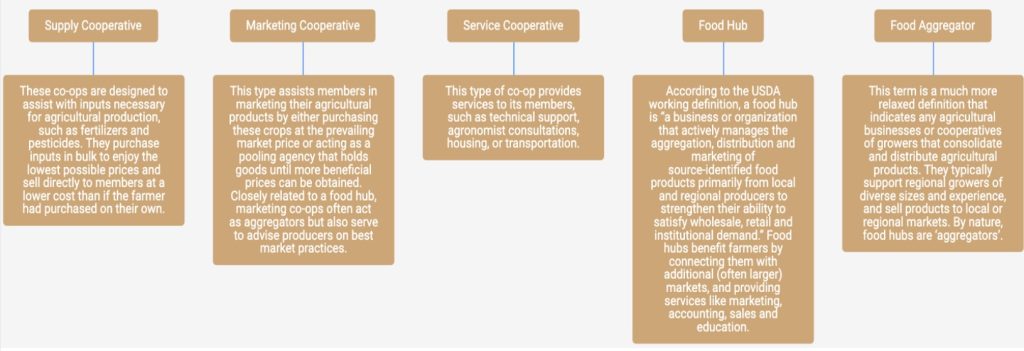

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) has attempted to classify cooperatives so as to understand and support their operations.1 The table below outlines a brief introduction to the current models of cooperatives operating within the United States, as laid out by the USDA itself.

“Co-ops are producer- and user-owned businesses that are controlled by -- and operate for the benefit of -- their members, rather than outside investors.” USDA

A co-op can fall into any one or a combination of these categories, and in fact many of them function within some sort of intersection.2 Though cooperative theory tends to have social benefits and identifying principles for groups, these terms must be understood to recognize how many farming communities survive within the operational margins of these current labels.3

The cooperative method does more than simply increase profit margins and bargaining power for small-scale farmers. These groups offer shared accountability that comes from dividing losses and profits evenly, while encouraging buy-in from farmers, funders, and consumers alike to cultivate paradigmatic change. Building on the cooperative ethic, agrarian coalitions work to mobilize the power of collective action in the face of shared struggles against racism, classism, labor exploitations, and land dispossession. The Rural Coalition/Coalición Rural (RC) and the National Family Farm Coalition (NFFC) stand as two key examples of such coalitional organizing: not only do both umbrella organizations encompass dozens of diverse member groups, such as the Federation of Southern Cooperatives/Land Assistance Fund, but NFFC has a novel and strategic shared leadership partnership with the North American Marine Alliance – linking aquatic and land-based organizing. Moreover, RC and NFFC, historically deeply aligned and collaborative themselves, both comprise key US members of the transnational agrarian network of La Via Campesina.4

Ultimately, this vast and growing network of multi-scalar cooperatives and coalitions provides a lens into what parity could look like, updated and expanded from its original iteration a century ago. NFFC has long centered agricultural parity, by name, in its advocacy, while Rural Coalition and other agrarian justice organizations have long centered fair prices for diverse farmers and fair working conditions for farmworkers. Going one step further, a closer look at key agrarian justice organizations shows how their cooperative structures articulate and actualize key principles of parity – though not in explicit name. Nevertheless, connecting commitments to fair farmgate prices, coordinated supply, and collective good demonstrates how frontline organizations are intuiting parity principles in innovative, resourceful, generative, and inspiring ways.

In order to reconcile the classist and racist policies the US agriculture system is built upon, we must look to those working the ground to inform our policy decisions nationwide. To examine a real-world example of what 21st century parity could look like, we look to World Farmers, a group that advocates for and supports immigrant, refugee, and historically underserved small-scale farmers from farm to market. A longstanding member group and leader within Rural Coalition, World Farmers’ model is not like a traditional farm incubator program, grower’s association, cooperative, or food hub; their services encompass all those roles and more. By understanding the nuances of their community-led, farmer-focused organization, we are able to see how parity principles – even those not named explicitly as such – can cultivate diverse, secure, and equipped communities.

World Farmers as a Microcosm of Parity – A New Cooperative Methodology

World Farmers’ mission is to honor the dignity and passion of immigrant and refugee farmers to grow food vital to their culture and communities, and to provide support to each farmer in their endeavors to do so. Organized as a nonprofit nearly three decades after programming initially began, their mission was not drafted, it was lived. The organization was developed out of need and program development continues to be driven and shaped by each program farmer. Their programming first began because of a refugee farmer's bravery in asking for land when her family and community had a great need, and the kindness of an immigrant farmer who offered land because they knew what it was like to lack. That land became known as Flats Mentor Farm. Now, World Farmers supports farmers along every step of the learning process, facilitating mentorship spaces across farmers and cultures and cultivating a shared space among individuals of like backgrounds so that farmers can learn together and from each other, and can be inspired by those who have come before them.

The organization’s Executive Director, Henrietta Isaboke, moved to Massachusetts with her family from Kenya in 2001. Her mother learned about and joined the Flats Mentor Farm program in 2004, and Henrietta farmed alongside her mother and father for years before joining the family business in 2010. Once she joined the World Farmers team, Henrietta left her family business to her mother who now brings her granddaughters – Henrietta’s daughters – to farm alongside her. This multigenerational agrarian approach is common in the Flats Mentor Farm program, an initiative which does not ‘graduate’ farmers from the land. World Farmers is working with the farmers at Flats Mentor Farm to develop a FMF Farmer Land Committee to build leadership and autonomy among program farmers, and where farmers may discuss issues that arise on the farm, make decisions on land management and infrastructure development, and engage with World Farmers staff to continue to shape their programming. At the moment, the organization operates six land sites totaling over 100 acres in Massachusetts. The FMF Farmer Land Committee facilitates leadership development and allows space for farmers to implement a community-based governance board.

As a nonprofit, World Farmers offers service beyond those of typical farmer training programs in the US.5 Farmers in the Flats Mentor Farm program seek land and opportunity to feed their families the crops of their culture and rebuild their family’s cultural roots. Many of them go on to build a sustainable farming enterprise, specializing in production and marketing of cultural crops to diverse consumers in Massachusetts and beyond. The program offers hands-on experience and assistance to the next generation of farmers and provides immigrant and refugee farmers a chance to contribute to their family’s health and wealth. In a four-phase mentorship program, farmers teach one another from their personal struggles entering new markets, experimenting with new crop production, all while fostering a spirit of comradery rather than competition.

One of the many services World Farmers provides to Flats Mentor farmers is access to wholesale markets through aggregation, sale, and distribution of products. Presenting program farmers with the knowledge that their product will be bought after harvest functions within the traditional cooperative methodology, but allows for extra benefits as well. For example, World Farmers works with the farmer to establish a fair market value for any new cultural crops they want to market, and takes on the risk of crop trials as they build customer familiarity and awareness of the new crop. For retail markets, if a farmer is thinking of growing a certain crop but is unsure of how well it will sell at market, World Farmers will coordinate a farmer to farmer exchange, allowing a producer to take another program farmer's product to market to assess saleability. This provides the producer with knowledge of consumer demand at low-risk to the farmer. This process is of particular importance as farmers are expanding to production of crops outside of their cultural expertise, increasing access for other cultural communities. Additionally, World Farmers assists with technology and equipment access and training of electronic payment softwares for producers who go to market, and signing up and maintaining certification and processing of programs which increase access for low-income consumers such as WIC and SNAP. World Farmers also provides hands-on support in production, post-harvest handling, and food safety certification to ensure all crops sold are up to market standard; and provides access to external resources such as USDA, including the NRCS EQIP High Tunnel program.

One of the many services World Farmers provides to Flats Mentor farmers is access to wholesale markets through aggregation, sale, and distribution of products. Presenting program farmers with the knowledge that their product will be bought after harvest functions within the traditional cooperative methodology, but allows for extra benefits as well. For example, World Farmers works with the farmer to establish a fair market value for any new cultural crops they want to market, and takes on the risk of crop trials as they build customer familiarity and awareness of the new crop. For retail markets, if a farmer is thinking of growing a certain crop but is unsure of how well it will sell at market, World Farmers will coordinate a farmer to farmer exchange, allowing a producer to take another program farmer's product to market to assess saleability. This provides the producer with knowledge of consumer demand at low-risk to the farmer. This process is of particular importance as farmers are expanding to production of crops outside of their cultural expertise, increasing access for other cultural communities. Additionally, World Farmers assists with technology and equipment access and training of electronic payment softwares for producers who go to market, and signing up and maintaining certification and processing of programs which increase access for low-income consumers such as WIC and SNAP. World Farmers also provides hands-on support in production, post-harvest handling, and food safety certification to ensure all crops sold are up to market standard; and provides access to external resources such as USDA, including the NRCS EQIP High Tunnel program.

World Farmers sees what true parity looks like as it organically grows from a community that values and prioritizes farmers. The immigrant experience in the United States is often an isolating, confusing, and lonely journey. That is, until one begins to build up a community of familiarity once again. Things like smelling a traditional meal being cooked, an offering with no expected reciprocation, or the kindness of a smile across a language barrier cultivates hope and belonging. When you bring together cultures that view agrarian knowledge as a sacred and vital way of life, you end up with a system much more nuanced and culturally influenced than a traditional cooperative or aggregator. You build a small family, a place for immigrant-immigrant knowledge transfer rather than expert-student transfer. Flats Mentor Farm exemplifies how current USDA terminology and definitions limit the understanding of parity principles at the community level.

Flats Mentor Farm as an Illustration of the Community-Driven Parity Example

While traditional cooperative and food hub systems offer market avenues, they do this from a perspective of business and economic viability. World Farmers, through its Flats Mentor Farm program, embraces the dynamics of market economics while relying on an underlying culture that emphasizes a strong sense of community, co-responsibility, and solidarity to drive parity in access to land, infrastructure, pricing standards, and competition among its members.

The Flats Mentor Farm model evokes and practices agroecological principles of “economic diversification, co-creation of knowledge, social values and diets, fairness, connectivity, land and natural resource governance, and participation”. These serve as a testament to the strength and resilience of agroecological principles in beginning farm operations and sustainable farming, even though World Farmers does not set out to establish itself as an agroecological model. Rather, the organization embraces these principles as part of the set of norms that govern the way they work, the diverse composition of Flats Mentor farmers, and their mentorship methodology that strives to incubate resilient farmers and business owners that can be self-sufficient. World Farmers’ emphasis on farmers’ accountability for their own parcel of land and the communal norms that all live and abide by provides for the conditions for food sovereignty in the microcosm of the World Farmers community. The values of solidarity, equity, integrity, and respect for the land creates the conditions for farmers to freely share knowledge and the psychological safety of knowing that the land they have is theirs to use. Furthermore, the phased mentorship allows for farmers to set their own expectations and aspirations, ensuring them land for self-sufficiency or land to build their food business and eventually guide them into acquiring their own land. In this sense, World Farmers acts as part of the safety net of the food system, allowing farmers to integrate, learn, grow, and become business people themselves.

The go-to-market strategy at World Farmers is also governed by the same values and agroecological principles that permeate the organization. This means that farmers self-organize to attend to certain geographic markets without meddling or intruding on each other, and agree to abide by set price floors. In fact, Flats Mentor farmers establish and agree annually to non-compete rules for operations at farmers’ markets and community markets, which allows each farmer to sell and build a strong customer base without direct competition from their fellow program farmers. By offering methods of continued education, business advising, and market protections, World Farmers embodies parity price floors and supply management, all from the farmer-first standpoint, rather than the rampant neoliberal economy-first perspective. These rules are uniquely accorded based on “handshake” principles. This works in the case of World Farmers because of the underlying values and principles they operate within. There’s a deep sense of moral obligation, but also a solidarity that binds the community together based on shared experiences.

Additionally, World Farmers helps guide farmers to access retail markets, as well as facilitating wholesale opportunities through aggregation and distribution activities, ensuring farmers a fair market price for their produce. It’s also important to note that planned crop planting is a complement to the farming operation without taking away the autonomy each farmer has in their business decisions. Many of the crops Flats Mentor farmers grow are culturally and personally important to them. The principle of respect for the land – the farmland and the motherland – is part of their mission, thus most farmers’ planting decisions are made first and foremost to ensure supply of cultural crops through the winter months for their families and communities. However, the immense solidarity among the farmers and strong cooperation among them allows World Farmers to engage and supply the market's food needs.

Conclusion

As covered above, the need for federal parity pricing and supply management is pertinent as we approach the next Farm Bill. The Flats Mentor Farm program of World Farmers is a glimpse into what parity can look like when we allow ourselves to learn from those on the ground, prioritizing farmers in a relational and honest way. Additionally, without centering racial and immigrant justice into our fight for parity, we miss an intersection that writes centuries of skilled agrarians out of the story. History will not only judge us for how we proceed, but also for who we leave behind. Parity is an inclusive fight for justice, agrarian viability, and opportunity for our skilled farmers to thrive within their desired profession. Without group missions like World Farmers, we lack ideas of community and collaboration that are strongly defined in other global cultures that we need for a holistic approach to food justice. In a country that often deliberately overwrites the history of how it came to be, it must be noted that healing and reconciliation are not yet complete within marginalized communities. This has led to a distrust that federal policies can work for farmers of color, making it all the more pertinent to call for intersectional agrarian reform.

As covered above, the need for federal parity pricing and supply management is pertinent as we approach the next Farm Bill. The Flats Mentor Farm program of World Farmers is a glimpse into what parity can look like when we allow ourselves to learn from those on the ground, prioritizing farmers in a relational and honest way. Additionally, without centering racial and immigrant justice into our fight for parity, we miss an intersection that writes centuries of skilled agrarians out of the story. History will not only judge us for how we proceed, but also for who we leave behind. Parity is an inclusive fight for justice, agrarian viability, and opportunity for our skilled farmers to thrive within their desired profession. Without group missions like World Farmers, we lack ideas of community and collaboration that are strongly defined in other global cultures that we need for a holistic approach to food justice. In a country that often deliberately overwrites the history of how it came to be, it must be noted that healing and reconciliation are not yet complete within marginalized communities. This has led to a distrust that federal policies can work for farmers of color, making it all the more pertinent to call for intersectional agrarian reform.

In a new, radical, imaginative space of a socially just era of agriculture, we must look to these communities building from their core values as models of inspiration rather than direct replication. While parity sets the foundation for livelihoods in agriculture, it does not take away the potential for communities to define their own pathways towards food sovereignty based on their cultural, social, and economic values and histories.

1 Krikorian, Jacqueline. 2022. Literature Review. “The Potential of Migrant Farming Cooperatives”.

2 The National Agriculture Law Center. “Cooperatives-An Overview”. The Nation’s Leading Source of Agricultural and Food Law Research and Information. 2022.

3 Royer, S. Jeffery. US Department of Agriculture. “Cooperative Theory: New Approaches”. Service Report 18. July 1987.

4 La Via Campesina comprises about 150 local and national organizations in 70 countries from Africa, Asia, Europe and the Americas. Altogether, it represents about 200 million farmers. La Via Campesina currently represents the largest organization of peasant workers on Earth.

5 Many farming programs in the United States allow people to be trained in agricultural production and entrepreneurship, but upon finishing these programs farmers have the potential to be left land-less. Thus, without the resources to continue their businesses, skilled farmers face the threat of extended careers as farm laborers, service workers, or other disenfranchised land-workers.