Table of Contents

Peaches. The first fruit my grandparents picked as immigrant farm workers was that fuzzy stone fruit. Agriculture is our culture. And resistance, our act of preservation.

I am the daughter of small-scale farmers from eastern Punjab. After struggling to make ends meet, my grandparents migrated to California in 1978. As with most uneducated Punjabi Sikh immigrant peasants, they picked fruit in the fields of Yuba City for little pay.

Growing up in a community of Punjabi Sikh immigrants so connected to soil and farming led me to represent migrant farmworkers in my first job as an attorney. The largest and longest sustained protest in my ancestral home inspired me to return to this work.

Over the past year of supporting the Indian Farmers Protest from afar and learning more about Disparity to Parity, it is clear that parallel agrarian movements all reflect back to one truth. To achieve fairness for food producers in our globalized food system, we must embrace parity as the unifying call. Parity is fairness at the farmgate and includes concepts such as price floors or minimum support prices, which are adjusted for inflation. This essay serves to connect the Indian Farmers Revolution to the common calls for economic justice in furtherance of a global farmers movement.

A Culture of Resistance and Nascent Farmer-Laborer Solidarity

Punjab, the land of five rivers, is well known as the food bowl of India, responsible for alleviating the people of a US “aid-driven" to “ship-to-mouth” existence. Since its annexation in 1849, Punjab has been a hub of agrarian resistance and state repression. The post-colonial selection of Punjab for the “green revolution,” which was far from green, strengthened US-led private fertilizer companies and India as a nation – at the expense of the soil, water and people of Punjab.1

The region has witnessed multiple agrarian movements demanding an increase in the Minimum Support Price (MSP) from the 1970s to the present. Mobilizing to unite against brutal dictators and capitalist agriculture is a living memory in the Punjabi ethos. The traditional songs, ceremonies, poetry, literature and general cultural vibe reflect this reverence for the land as a great mother. Pavan Guru Pani Pitha, Matha Dharath Mahath. A simple translation of my favorite Sikh scripture teaches us that the Air is the Guru, Water is the Father, and Mother Earth is the greatest of all. This sentiment explains the steadfast commitment amongst the farmers to their cause.

On June 5, 2020, the right-wing government led by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) promulgated three “farm bills.” In reality, these “farm bills” were privatization laws designed to deregulate India’s agricultural sector. Under the guise of much needed economic reform, corporate houses, such as Ambani and Adani, could hoard grain, easily purchase farmland and control a market - free of taxes and a price floor. The Indian farmers accurately interpreted this strategically timed corporate handover as a direct threat to their livelihood.

In a classic case of disaster capitalism, these bills were rammed through the Indian parliament in September 2020 during a nationwide lockdown. The video footage shows the chaotic repression of debate and discussion. Procedurally flawed, these bills became laws in an undemocratic fashion, devoid of due process. And substantively unlawful, it was also an unconstitutional encroachment by the central government in an area it lacked jurisdiction. Under the laws of India, the subject of agriculture is solely within the purview of the state governments.

Anti-worker legislation has made it tougher for workers to organize, increased work hours and removed overtime protections. These measures to weaken labor laws are advanced to attract foreign investment. In the capitalist agriculture system, low wage workers and peasants are “inextricably linked”. The potential for class unification under the common banner of much commentary and analysis has been devoted to this unique feature of the farmers' revolution: farmer and farmworker solidarity.

Kisaan Mazdoor (Farmer Laborer) labor unions led a strategic organizing campaign. This unique and previously unforeseen alliance between farmers and landless farmworkers forged a formidable opposition to the extractive economic agenda of the Modi regime. In many ways, their struggles are interconnected, sharing parallel threads to a globalized food system where “farmers are going bankrupt while people are going hungry.” Arguably, “farmworkers'' is a more accurate term to describe the farmers of this historic resistance. The average Indian farmer owns one to four acres of land. According to the World Trade Organization (WTO), 99.43 percent of Indian farmers are low income or resource poor. It is an ironic picture when those who feed a nation go hungry.

Summary of Key Developments from the Morcha

The “Dilli Chalo” (let’s go to Delhi) movement was the outcome of an entire season of organizing in summer 2020 by farmer unions in the states of Punjab and Haryana. They visited villages with pamphlets explaining the three ordinances in detail. These tactics to mobilize the peasantry are strikingly similar to the hallmark practice of “house meetings,” among the United Farmworkers Union fighting for dignity and equality under the leadership of Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta in California. Other notable techniques and strategies are described further below.

Fall 2020

The resistance grew in September 2020 during “Rail Roko,” where farmers and laborers blocked the railroads in Punjab at multiple junctures. They blocked toll plazas and protested in front of the offices of elected leaders against the passage of these laws. Over the next several weeks, previously disjointed farmers unions and organizations would begin to unite and coalesce.

In late October 2020, the growing alliance, which included the All India Kisan Sangharsh Coordination Committee, gave a call for the farmers to hold a “chakka jam” (road blockade) on November 5. By November 7th 2020, 32 disparate farmer unions joined as one to form the Samyukt Kisan Morcha - a joint alliance to lead hundreds of thousands farmers in a long fight. Morcha refers to an organized rally in Punjabi. Kisan Ekta Morcha is the main digital arm of the farmers protest and is the mouthpiece for SKM. A call was issued for the farmers to prepare for “Dilli Chalo” (let’s go to Delhi) on November 26.

The national shutdown was jointly organized by ten central trade unions representing over 250 million workers across multiple sectors. The General Strike on November 26, 2020, was the largest nationwide strike in world history. Workers hailed from the public sector, transportation, banks, insurance companies and retail. In a powerful display of unity, the workers of India chanted: “[w]e are with the farmers.”

Rural farm in the US (top left) and scenes from the tent-cities at the Delhi border. Image Credit: NFFC Library and Indra Shekhar Singh.

This massive demonstration was a direct response to oppressive labor laws rammed through by the Modi regime in a similar fashion to the farm laws. Here, we see more seeds of inter-sector solidarity sprouting between the urban worker and the rural peasantry.

Hundreds of thousands of farmers from Punjab, Haryana, Uttarakhand and other states began a caravan of tractor-trolleys, jeeps, cars and motorcycles with Delhi as the final destination. Over the next few days, a mass movement of farmers marched towards Delhi but were blocked by hundreds of thousands of armed police and paramilitary officers firing water cannons, rubber bullets and tear gas. Even the elderly were not spared from lathi-charges (physical attack by police baton). These farmers persisted past fourteen-foot-deep ditches dug to trap their tractors.

Instead of acquiescing, the protesting farmers decided to indefinitely occupy the locale in which they were blocked. On the highways leading to the Capital of Delhi, they built tent cities, fully prepared for the serious long haul with rations, tools and equipment.

In late November 2020, more than 20,000 women reached the Tikri border protest site led by a female farmers union president, Harindher Bindhu, President of BKU. Bindhu epitomizes the umbilical link to land ubiquitous among the protesting farmers. She explained that “the government wants big farms, with big machines, like in California…the land is our mother. It’s our sustenance. It’s worth our life.” Over the next few weeks, farmers occupied more toll plaza sites and an additional tent city bloomed on the Shahjahan freeway entrance.

On November 27, 2020, I joined other Diasporic Punjabis, before the Indian embassy in Washington, D.C., to protest the brutal human rights abuses against peaceful protestors. Both international and intergenerational in scope, Indians from the diaspora of all ages engaged in protests from “kisaan sleepouts” on metropolitan streets to car rallies during the height of COVID 19. An activist lawyer from England, Daljit Singh, said that “[o]ur voices are our weapons….We are not going to abandon our elders who have been fighting on the frontlines.”

Art is a tool for solidarity building. The collaborative art series led by Oakland-based South Asian female graffiti artist, Nisha Kaur Sethi, is just one of many ways in which Diasporic Indians engaged in creative advocacy online. The purpose of the series was to raise awareness that “over a quarter of a billion people are organizing for farm workers rights and fighting to protect the Earth from corporate greed and government corruption.” Another aim of the series was to build solidarity between India and the global diaspora.

Protesters at the “March on Washington for Human Rights” in Washington, D.C. on March 20, 2021. Image Credit: Gayatri Malhotra on Unsplash.

We mobilized across oceans and time zones and became “morcha siblings” from the “Third Punjab” made up of the diaspora outside of eastern and western Punjab. A revived sense of community was formed online. Some of us were retriggered with the unprocessed trauma and pain of the Sikh Genocide of 1984, the partition of 1947 and countless struggles in between and thereafter. But in organizing and supporting the movement from afar, we began to heal intergenerational wounds with a sense of jazba (passion) and himmat (courageous effort).

Winter 2020

On December 9, 2020, Congressman John Garamendi (D-CA) and others wrote a public letter to the US Ambassador to India, Taranjit Sandhu, against the violation of the farmers’ rights to peaceful protest. A few weeks later, the US Congressional Record would memorialize the words of Congressman Andy Levin condemning what he termed state sanctioned violence against the peaceful protestors.

Others would tweet and offer soft support but no one directly called out the elephant in the room. The substance of these laws that stood to enrich corporate agriculture was never challenged. Instead, the governments of the United States and Canada signaled support for these laws as efficient market reform.

That winter many farmers suffered from the bitter cold and some even froze to death. A death toll ticker website was created by a daughter of farmers, Anoroop Sandhu, to memorialize the martyrs of the movement.

On January 26, 2021, the Modi regime celebrated an opulent 72nd anniversary of India’s constitution while thousands of farmers marched on foot and on tractors from their tent cities on the highway through the unfamiliar streets of New Delhi. I watched that day with a twisted stomach as the local Punjabi news aired footage of police violence against protesters. Tensions further escalated earlier that morning when the barricades were not removed at the previously stated time. Farmers on the ground recounted the chaos which resulted from the protesters being intentionally ciphoned to unfamiliar routes. Most of these farmers had never stepped foot outside their villages until this mass movement.

Although Wikipedia accounts paint the protesters as having “deviated from the pre-sanctioned routes” there is no account of the police violence preceding this event. Recently married 25-year-old Navreet Singh was shot while on his tractor, but the truth was covered up by the Delhi police. A doctor from Mandeep Punia, was arrested and tortured for trying to do his job.

The lifting up of the Sikh flag, known as the Nishan Sahib, at the Red Fort became a splintering issue threatening to derail the movement. Scenes of police and protestors in conflict went viral. The Modi regime responded with Internet shutdowns, barricades blocking toilets and deadly metal spikes on the border sites.

The protesting farmers have suffered under a constant stream of First Information Reports (FIRs), which are initial documents filed by law enforcement to trigger criminal investigations of alleged offenses. The criminal justice system was strategically employed to slow down and squash the momentum. Police brutality is the norm and not the exception for most dissidents in India, as well as journalists and labor union representatives.

In early January, local police in Haryana arrested Nodeep Kaur, a 23-year-old labor rights activist, on false charges in retaliation for asserting her right to represent unpaid workers. Her sister confirmed that law enforcement had brutally beaten and sexually assaulted her. Nodeep is from a poor Dalit family of Punjabi Sikh heritage who devoted their lives to advancing the rights of working class communities. Her union, the Majdoor Adhikar Sangathan was in her own words, “perhaps the only workers’ body in the country to have blocked roads and obtained free rations from the government during the COVID-19 lockdown.” She became the face of the movement. Nodeep chose to remain at the Singhu border upon her release from jail in February 2021 alongside her friend and fellow labor activist Shiv Kumar.

Stories of agrarian resistance in the Global South rarely break through the American news cycle. The largest and longest protest in the world went unnoticed for months until a few days after the tumult of January 26, 2021, Rihanna tweeted: “why aren’t we talking about this?!” The pop star icon and soon to be mother, shared a CNN article about the Internet shutdowns and human rights violations of farmers.

Climate activist Greta Thunberg tweeted the same CNN article as Rihanna and also shared the renowned toolkit. The link to the “toolkit” is still live and powerfully connects agrarian justice to climate justice. It highlights the parallel struggles of rural communities all over the world facing the same patterns of privatization. In hindsight, it also fits into the framework of a toolkit for food sovereignty. The toolkit states that this movement extended beyond “one country and its oppressed peoples,” to “common people across the world having the opportunity to be self-sufficient, feel secure about providing for their families, and live well.”

The toolkit drama mutated into a witch hunt for a 22-year-old climate activist, Disha Ravi, accused of creating the toolkit. Multiple tech companies capitulated to the demands of the growing fascist government of India by sharing the communications amongst this group. Groups of angry Indian men burned photos of global female influencers because of their support of the farmers' protest. Sensitivity to image runs high among the BJP and its supporters.

The Modi regime did a sloppy job of trying to shift the narrative with heavily curated tweets by Bollywood puppets labeling the supportive tweets by non-Indians as propaganda. However, the Sikh Coalition, a US civil rights organization, worked behind the scenes to push a positive narrative among several media outlets including: NowThis, The Guardian, Reuters, CNN, and several others. Nearly 7,000 residents joined their online campaign to ask elected officials in Congress to support a resolution in support of the farmers.

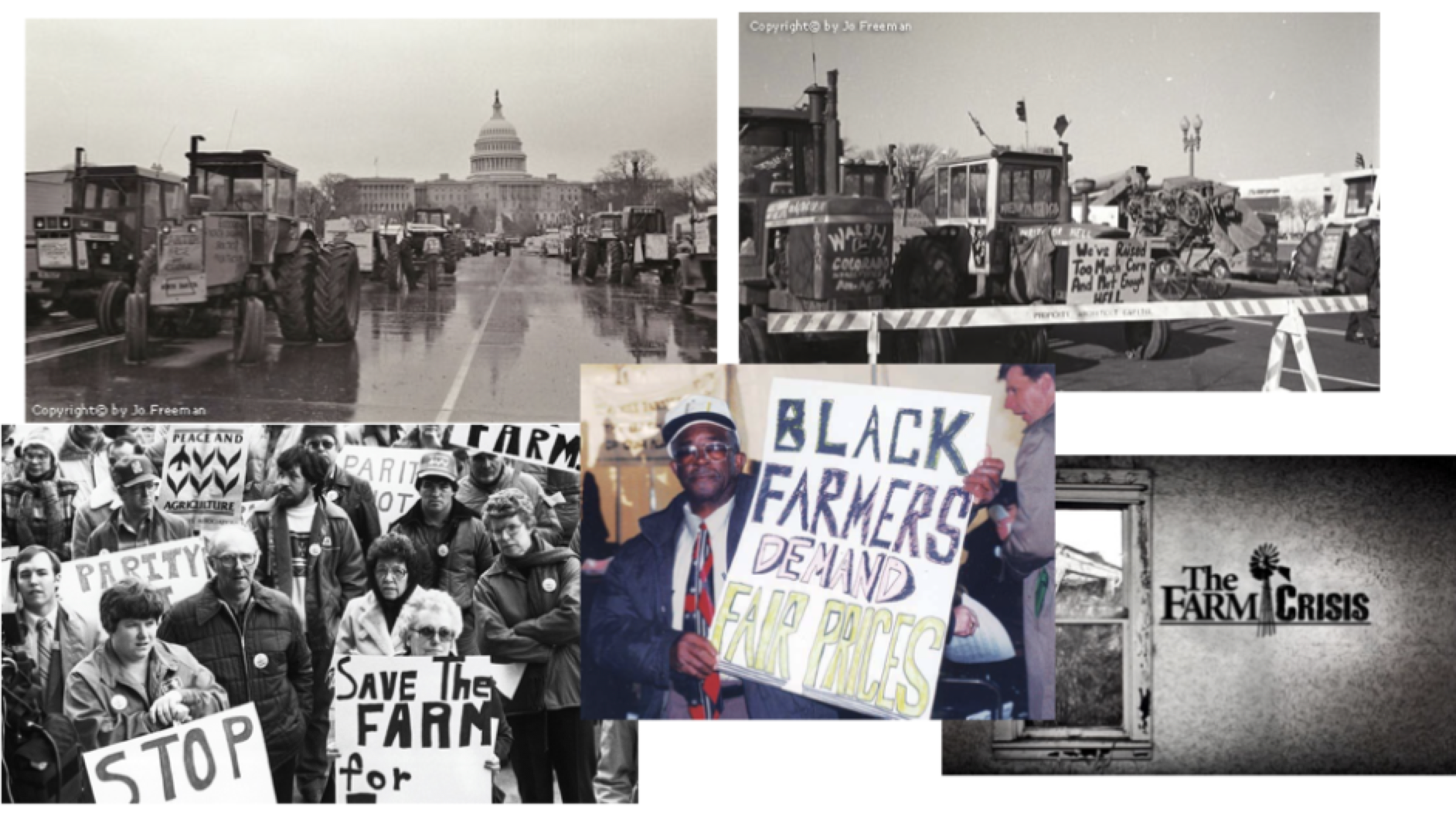

February 2021 was a busy month. We worked with We Support Farmers and Kisan Ekta Morcha to organize a six hour global webinar viewed by more than 22,000 people. Joel Greeno, from Family Farm Defenders, was one of several speakers who shared lessons from the American farmers’ battle with similar farm laws. He shared that in 1979, 60,000 farmers came to Washington, D.C. on their tractors to demand fair pay and access to the market. Mr. Greeno emphasized that “the citizens should consume the food produced by the nation’s farmers,” an anchoring principle of food sovereignty.

Image Credit: Kisan Ekta Morcha

We also shared a video of solidarity from Cassia Bechara on behalf of 600,000 members of Brazil’s Landless Workers Movement (MST). She stated that the farm laws passed in India “will only benefit export agriculture and agribusiness...but we know that only peasant agriculture can supply food for the Indian people.” She acknowledged their suffering in the cold rain and said do not give up, ending with “globalize hope” – a common slogan among La Via Campesina members.

Dr. Garrett Graddy-Lovelace revealed the dual impact of the neocolonial Green Revolution and neoliberal free trade policies on the commodity crop surplus. Dolores Huerta, the legendary community organizer and founder of the Dolores Huerta Foundation, shared her experiences fighting for landless farm workers in the United States. More than 17 million people boycotted grapes and lettuce in solidarity with them. She explained that it took five years of organizing to win decent wages, collective bargaining and toilets in the field. Huerta ended with a call to not quit and her famous signature line: Si Se Puede! (Yes we can!) Later, she would share an open letter to President Joe Biden and continue to support the farmers' protest.

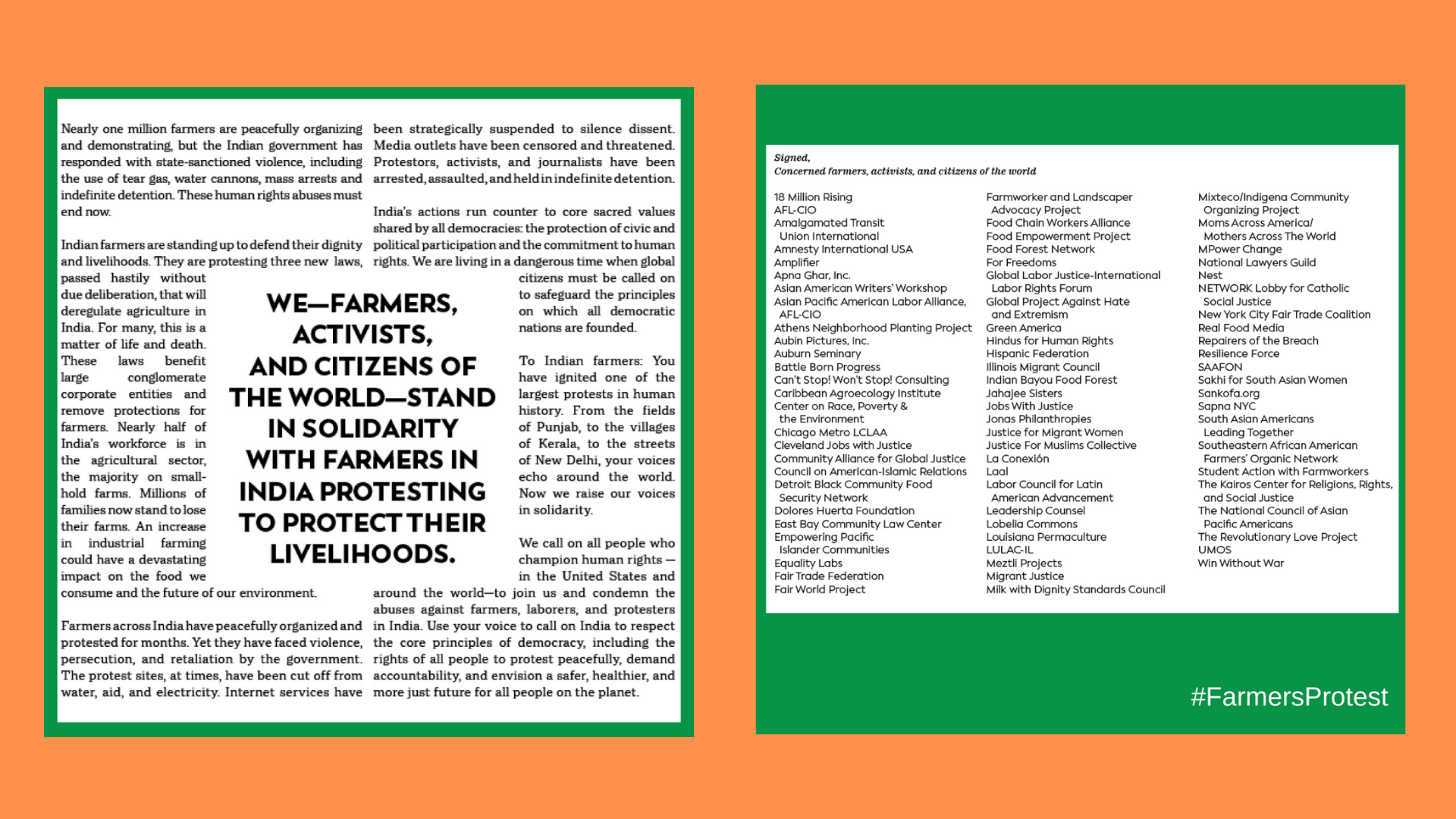

This month was also buzzing with solidarity and support. On February 23, 2021, eighty-seven US-based organizations including the National Family Farm Coalition (NFFC), Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy (IATP), A Growing Culture and the Community Alliance for Global Justice issued a solidarity statement in support of the protesting farmers. Their aim was to make the connections between the forces of neoliberalism that attack family farms in both India and the United States. The solidarity statement boldly condemned the liberalization of markets without protection for small farmers from corporate buying power. Jim Goodman, NFFC Board President, captured this sentiment by sharing that “[w]e have been forced to accept low farm prices and we support their demands for economic parity – fair prices and living wages – to defend their livelihoods, their food sovereignty and the future of their republic.”

Image Credit: Justice for Migrant Women

A few weeks later, I joined about thirty other US attorneys of South Asian descent in publishing an open letter to President Biden in a major Indian newspaper. We have yet to receive a response. Around the same time, Justice for Migrant Women published a full page ad in the New York Times with the names of 75 organizations in support of a powerful statement of solidarity. An accompanying video hit home that non-Sikh and non-Asian voices were sounding the alarm on the human rights violations of Indian farmers.

Spring 2021

In March 2021, the Delhi police arrested a group of 25 Sikh women from the Singhu Border, including a two-year-old child, who refused to remove flags representing the Farmers' Revolution and Sikhism (the Nishan Sahib) from their vehicle.

On March 21, 2021, the New York Sikh Council organized a “March on Washington for Human Rights,” marking more than 100 days of peaceful protest amidst gross human rights violations. Hundreds of protesters from across the eastern seaboard participated. Jordan Treakle from the National Family Farm Coalition and Dr. Garrett Graddy-Lovelace gave inspiring speeches to connect the struggles of Indian farmers to small farmers struggling in the United States.

In May 2021, Freedom House in its annual report on civil rights and liberties worldwide downgraded India from a free democracy to a “partially free democracy” on decline since Modi came into power in 2014. Freedom House pointed out that The Economist Intelligence Unit described India as a “flawed democracy.” Both institutions express grave concern about the impact of Modi’s Hindu nationalist government on democracy in the world.

Summer 2021

On June 2, 2021, the Ethnographies of Empire Research Cluster at American University’s School of International Service held a webinar to discuss the farmers uprising in India as a tipping point in international agriculture policy. This webinar explored how empire is reproduced, formed and contested within the context of the privatization laws being challenged by the Indian Farmers Revolution. The keynote speaker, Devinder Sharma, award-winning Indian Journalist and Food and Trade Policy Expert, highlighted how the modern food system compels nations in the Global South to move people out of the rural areas and into urban enclaves. But, reducing the number of farmers in agriculture does not increase farm income. He cautioned the Indian government against following the US model where continual farm size increases have eradicated many family farms.

On the ground in India, in late June, ten central trade unions in India held a day-long protest nationwide in solidarity with the farmers. On August 28, 2021, farmers peacefully protested with black flags at a toll plaza in Karnal against a BJP meeting by blocking access on the highway. When the farmers refused to move, the Haryana State police used force with batons or “lathi charges” resulting in serious injuries requiring hospitalization.

By September 11, 2021, a five-day standoff between farmers and the local government in Karnal, Haryana ended when the government agreed to investigate the August 28th incident of police violence.

Fall 2021

September 2021 began with a new strategy by the Indian farm leaders to apply electoral pressure against the BJP ruling party in the 2022 state elections. This strategy proved successful in the State of Bengal. We would see pictures of farm leaders traveling to various election hot spots, speaking in front of massive crowds, in jubilant spirits.

On October 3, 2021, our hearts would sink yet again. Video footage went viral of BJP politician, Ajay Mishra Teni’s son, in a SUV killing eight people, including five farmers during a peaceful march in Lakhimpur, Uttar Pradesh. This brutal attack, in particular, occurred just days after the BJP politician Teni had publicly instigated violence against the farmers. Public outcry led to the eventual arrest of Teni’s son. But, the farmers continue their demand for his father to be removed from office.

All things would shift on November 19, 2021. Earlier that day, we presented an abstract entitled “Disparity to Parity to Solidarity: How Agrarian Movements Resist Corporate Capture in the “Capitalocene” at the Critical Food Studies Conference hosted by a few universities in South Africa. We featured a rap video with insightful lyrics co-written by Indra Shekhar Singh and Young Daku, a rapper based in India. Later that same day, on a zoom call with fellow activists, we discovered that the farmers of India won part of their demands after nearly one year of sleeping in tents along highways at the borders of Delhi. We were stunned, in disbelief, and then immediately concerned that Modi had not legalized the right to MSP.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi publicly announced the repeal of the three laws – without any debate or discussion. Modi apologized to the citizens for being unable to convince the farmers of the benefits of privatization. He made no mention of the 726 farmers whose lives were lost during this avoidable resistance, nor did he acknowledge the brutal murder of innocent farmers by the son of a BJP government official. About ten days later the Indian Parliament formally repealed the three farm laws based on a majority vote.

Many people ask why Modi backed down. More likely than not, this was a strategic chess move to secure long term electoral control. Others argue that the repeal was an ideological attempt to distinguish Sikhs from Muslims within the Hindutva ranks. Nonetheless, as Professor Navyug Gill explains, it is undisputed that “constant protests led by diasporic Sikhs in front of Indian embassies and consulates” combined with growing solidarity worldwide formed an anvil of pressure.

The farmer union leaders agreed to end the farmers' protest, for the time being, on the basis of promises made by the BJP led government. Not surprisingly, none of these promises have been kept. There has been zero progress on the committee to discuss the MSP. Many other promises have been broken. This led to a National Day of Betrayal action on January 31, 2022.

Fairness for Food Producers: Price Floors as Parity

Patti Naylor, an organic farmer from Iowa, describes the value of a fair price at the farmgate as the recognition that “food and farming have a unique role in how people relate to each other and how we live on this planet.” The crux of the cries from the French farmers hanging dummies in front of parliament to the Indian farmers who camped out on the highways of Delhi is simply, fairness.

What is MSP?

A minimum farm price floor is as woefully overdue in agriculture as is a livable minimum wage under federal law. (The federal minimum wage in the US has been frozen at $7.25 for more than a decade).

In 1966, the Indian government established an Agricultural Produce Markets Committee (APMC or mandi yard) system where the government would buy staple grains from farmers at a guaranteed Minimum Support Price (MSP). This price benchmark was offered to persuade the farmers of the “food bowl” in Punjab and Haryana to grow the fancy new and costly seeds from the US as a means of reaching food security. Rice, for example, was not part of the traditional regional diet but became heavily over-produced, contributing to depletion of the water table. Ironically, the MSP as a price floor that on its face should uplift farm justice, in practice acts as a sword in severing the Indian farmer from local natural crop patterns and traditional agricultural practices.

Although the MSP program only applied to wheat initially, it was later expanded to the current list of 23 essential food crops. Yet, only six percent of Indian farmers actually benefit from MSP prices. This number is low because the government favors commodity crops like wheat and paddy grown in Punjab. Many farmers from neighboring states travel to the mandis in Punjab because there is a guaranteed price floor, or MSP, which is lacking in their home states. Many of the small farmers in Bihar have suffered from the lack of a price floor. They have been forced to leave the life of farming to join the droves of landless laborers.

This fight is not new. Solutions by Indians for Indians have been proposed, and gather dust on shelves in the form of the Swaminathan Report or the Rameshan committee report. As the cost of inputs and labor continue to rise, so has the intensity of the farmer movements. From the 1970s, 1980s, 1990s and 2000s, the tempo of agrarian resistance has not weakened but grown stronger with the decade.

In the early speeches from the border, the farmers of India demanded that the World Trade Organization (WTO) get out of agriculture. They are acutely aware of the corporate interests who have hijacked the world’s “trade” agreement process with the goal of maintaining binding and enforceable rules that shield their investments and profit margins. The WTO trade rules conflict with the ability of nations to customize agricultural policies that support their farmers and ensure food security. These rules are intended to keep farm prices locked in at low prices everywhere so that all food systems are dependent on international trade. Relatedly, the United Nations Special Rapporteur, Michael Fakhri has openly blamed the current trade system for prioritizing commercial transactions while ignoring the right-to-food perspective.

Genuine agrarian reform that serves the interests of the rural food producers is not to be found among the international trade and financial institutions. Both the Chief Economist at the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Gita Gopinath, and the Director of Communications at the IMF, Gerry Rice, have supported the three Indian farm laws as welcome agricultural reform to “improve efficiency.” These officials offer vague “job market accommodations” as solutions during the transition period to a privatized food system, but remain silent on the Indian farmers’ demand for a legalized MSP.

A critical section of the solidarity statement issued by NFFC and others helps to explain the silence from the Biden administration. In recognition of the role played by the United States in setting the stage for these farm laws in India, it stated in pertinent part:

“The US has been a key opponent of India’s limited use of MSP at the World Trade Organisation, arguing that it represents an unfair subsidy. Yet, the US government spends tens of billions of dollars on its agriculture, much of it in programs that directly contribute to low prices and commodity dumping in international markets.”

US foreign policy has often leveraged international trade rules and agreements to challenge how other nations protect the people at the bottom of the food web: the farmers and the hungry. The interests of the rural poor are often sidelined for the more expansive interests of our export-based agriculture system.

The failure of the free market to prevent farmers worldwide from floundering under the “cost-price squeeze” has worsened global food security and widened income inequality. The farmers of India, and indeed the world, deserve fair prices at the farmgate. The MSP should serve as a benchmark for domestic and international trade policy because it assures the existence of the rural world. It is time for India to codify the minimum support price as a price floor and broaden its scope beyond commodity crops.

What is Parity?

Parity is an overarching goal post. A guaranteed price floor, adjusted for inflation, is one of many stepping stones towards the quest for parity. As described here, the path to parity requires a radical restructuring of the “free market” economy that prioritizes corporate profit over the wellness of people, animals and the planet.

Collection of photographs from the tractorcade of 1979 and related protests nationwide. Image Credit: Dr. Garrett Graddy-Lovelace.

Without strong resistance movements, the cycles of capitalist agriculture continue to expand, extract and exploit. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the rural communities in the United States suffered a wave of economic calamity caused by the double whammy of rising costs and failing prices. More people farmed at this time with nearly a quarter of the population involved in agriculture. Farmers organized. In North Dakota, farmers formed the Nonpartisan League in 1916 and boldly stormed the State Legislature. They were successful in deflating the economic power of the grain monopoly by forming a publicly owned bank and wheat mill. But, such victories were few and far in between, and were not at the national level. A second wave of economic duress hit farmers during the Great Depression of the 1930’s where prices for crops crashed further, contributing to widespread food shortages.

Out of obstacles are born new opportunities. In 1933, the US enacted the first farm bill as part of the New Deal to provide farmers with price parity, which roughly translates into the protection of their purchasing power. Advocacy by farmers and their allies led to tangible victories in the form of price floors, production quotas, and non-recourse loan programs. Other features of the supply management program included acreage set-asides to incentivize farmers to stop farming certain land, inventory reserves, and price supports. Strikingly similar to the system in India, a national grain reserve was established to prevent prices from dropping too low in the event of a drought or other natural disaster. The US had created a system that guaranteed a minimum price for farm goods to meet the farmers’ costs of production.

As the power of consolidating agribusiness grew, their influence extended to the halls of Congress, where all vestiges of price protection for farmers were removed by the 1990s. Farm income immediately dropped. The USDA supplied direct payments but these subsidies went to the largest landholders. As Dr. Graddy-Lovelace explains, subsidies do not cause the crisis of overproduction but operate more as a “band-aid on the wound of overproduction.”2

Parity is the opposite of disparity. This term belongs in your forward thinking and solution oriented lexicon. On November 30, 2021, IATP hosted a global webinar entitled “Disparity to Parity to Solidarity: Justice in International Trade & Ag Policy.” Each speaker expanded the scope of how parity is more than just fair prices at the farmgate. Devinder Sharma added that agrarian distress is a product of economic design. The debt to death cycle has produced more than 400,000 deaths by suicide of farmers in India over the past two decades. This all occurs despite record-breaking food and dairy production.

In the US, the removal of price parity and supply management policies has led to low prices for farm products and a gargantuan windfall to corporate farms engaged in livestock production. This translates into skyrocketing debt for the average farmer. The toll of this debt is represented by an escalating suicide crisis in rural America. Farmers in the US are 3.5 times more likely to commit suicide than the general population. The economic and social impact of non-parity runs alongside the ecological consequences of failed agriculture policy: soil disease and erosion, groundwater pollution, and biodiversity loss.

This crisis is screaming for structural change. A cooperative and solidarity economy rooted in a culture of care has the potential to strengthen relationships between food producers and other sectors and segments of the community. It is the strength of these relationships that will determine the tempo and the tenacity of our will to transcend beyond the toxic industrial model of agriculture.

Building a Global Farmers Movement for Justice

There are parallel agrarian movements happening in real time from the landless farmers in the Philippines to the tractor marches in Spain to the worldwide counter-mobilization against the United Nations Food System Summit. The common thread connecting these pockets of resistance is a food system fortified by a “free market” formed to further neo-colonial methods of extraction through finance, trade and agricultural policy. With the threads connected among and between these struggles, we can strengthen the global farmers' movement for justice.

Image Credit: A Growing Culture

A global community organizer recently said to me: “solidarity and collaboration are truly the pillars of resistance.” Acts of solidarity should not attempt to speak for those on the frontlines of struggle, but, solidarity as a practice in movement building offers recognition, empathy and appreciation. Extending solidarity is also an acknowledgement of gratitude for the inspiration.

Leaders from Nigeria to Wisconsin to Iowa to the San Joaquin Valley are all sharing the same message: we are watching, we still stand with you, we see you. Countless solidarity videos of support and the La Via Campesina campaign to “Salute the Indian Farmer” all reflect this deep sense of recognition, gratitude and appreciation. A consistent theme is this common respect for the steadfast courage and the scope of sacrifice exhibited by the protesters.

Taking these connections further to clearly establish the co-dependent demands for economic justice at the farmgate is the next step. World-renowned political dissident, linguist and author Noam Chomsky contextualized the farmers' movement as a “beacon of light for the world in dark times.” This light has illuminated the power of sustained resistance. Another world, with fairness for farmers all over the globe, is possible.

![]() Reflections on the World’s Largest and Longest Protest: Parity as the Unifying Call by Daljit Kaur Soni is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Reflections on the World’s Largest and Longest Protest: Parity as the Unifying Call by Daljit Kaur Soni is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0